The Dan O'Connell

What is the Melbourne Poetry Scene (aka Melbourne Spoken Word Scene)?

The scene essentially consists of all the folk who regularly show up and read at the staple poetry venues in Melbourne. They are, of course, not the only people in Melbourne who write poetry – who knows how many secret poets are out there, shamefully writing away in the dark, their tortured faces illuminated by the anemic glow of a Macbook Pro (even Gina Reinhart seems to do it [please god make it stop]). The ‘scene’ doesn’t necessarily represent those whose poetry has been published, many are purely spoken word performers and don’t even want to be published on the page (calm down, it’s radical thinking I know). It’s a grass roots concept and as such there is no established hierarchy, though you may find yourself wielding some influence as the organiser of a gig, but beware that beautiful yet deranged beast that is the Poet Ego (more on this later.)

How to get involved:

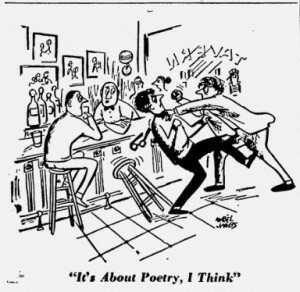

You assert yourself in the scene through participation, and it is as much about socialising and drinking as it is about poems. (Pro tip: try to avoid dating poets. Poets dating poets is like crossing the streams in Ghostbusters. It will end gross and slimy, in a bad way.)

As an enthusiastic poetScenester (imagine, high angle MySpace pics with a quill in your cleavage) your dedication to your craft and your skill is rewarded with Features - featured readings starring YOU! FINALLY. A ROOM FULL OF PEOPLE STUCK LISTENING TO YOUR STUFF FOR TWENTY OR SO ODD MINUTES – HELLO SUCCESS. If you’re lucky, this will be a paid gig. The popular misconception is that features are something you earn just through quantitative participation, as if you keep turning up they’ll eventually have to give you a go. But this is not high school softball and this is without any analysis of what that means and why venues even feature the Features.

Bring it!

The Feature is an opportunity for a venue to draw in a crowd, the poets are meant to be good at poetry and interesting for the punters. Being the feature is an acknowledgement of the quality of your poetry (whether this be consistently brilliant, or steady improvements) as well as your performance skills. This point is rather contentious with the obvious division between the ‘page poets’ and the ‘performance poets’. Regardless of your personal preference the fact remains that the two require some crossover, but they are not mutually exclusive or both steadfast requirements. Part of the featured poet’s job is to entertain – whether this is through offering solemn or thoughtful verse, or rollicking, shocking performance. The job is to leave your audience with an impact, either something awe-inspiring to ponder or to enjoy through deep belly laughs. The open mic is a democratic system in which anyone may perform. As a feature, you are the entertainment. In media terms, you are the content. You gotta deliver.

Etiquette:

Sweet Talkers

Feature gigs are not just for your own vanity. Yes, as poets we are horrendously self-aware, -conscious, -flagellating, -aggrandising, but any artist who respects their craft knows that it is with the craft they must be first concerned. The scene is also a community, which means being conscious and courteous of other poets and their work. If you want the room to pay attention when you’re on stage, pay the obvious respect of listening to others. There is little else more disheartening and goddamn annoying for a performer than a loud, uninterested and ultimately rude crowd. And anyway if you want to be famous, you’ve chosen the wrong path, kiddo. I don’t know when Australia’s Got Talent is on, but you’d have a better chance on there.

It’s important to remember to not let your ego come through your work when at a poetry open mic gig. If it is an explicitly stated five-minute limit, do not exceed five minutes. You might be able to get away with this by charming the room, but remember that the time you use up means someone else won’t get a chance to read, or the evening will run too long, resulting in people leaving and missing the last on the list. Time limits are not designed to restrict your creativity, rather they ensure a well paced event. Remember you can wow a crowd in one minute as well as you can with five.

And finally, enjoy it. The Melbourne scene has so many wonderful gigs in some damn fine establishments, and the poetry from these fine, creative individuals is both hells enjoyable, and consistently inspiring.

Go Forth and Poet!

If you would like to check out some excellent poetry in Melbourne town you can get along to any of these regular events listed on Melbourne Spoken Word, Pam’s Poetry Pitch, Melbourne Poet’s Union. Keep a look out for this year’s Overload Poetry Festival.

Jessica Alice is a writer, editor and broadcaster from Melbourne. She hosts Spoken Word on 3CR 855AM and is the Poetry Editor for Voiceworks. Jessica is a regular guest on Triple R’s Aural Text and produces a segment on the podcast Nothing Rhymes with RRR. She is currently writing her Honours thesis on the work of contemporary American poet Johanna Drucker. Her most beloved possessions are her bookcase and her Buffy boxset.