No Abandoned Cow: Ada Limón on Poetry & the American Road

For the most part, I feel like I have no idea what I’m doing. I don’t mean with poetry, or with prose, but with life. Most days, there’s a devilish beast at the bottom of my spine telling me I’ve got it all wrong. What have you done with your life? Little selfish word-eater, time-waster, navel gazing narcissist. Get a real job. Help someone. Do something. Solve problems. Grow up. But other days, especially when I’m on the road and sharing poems with strangers, I think it’s all going to work out, and that in some ways I am helping, even if just by pointing at the pain and the joy and saying “Yeah, me too. I see it, too.”

The most recent poetry tour was 1335 miles, 11 events in 8 days, and 9 total days of car travel. When traveling with 2 dear friends and poets, Adam Clay and Michael Robins, and writing a poem every day for National Poetry Month, and meeting up with other knee-deep poetry makers on the road, it does begin to feel like, well, like dropping acid. Everything feels a bit more psychedelic and nothing’s not moving or breathing or shoving itself into a poem. No abandoned cow, no unsung greasy grackle, no roadside attraction unworthy of more words. How good it is to leave your small safe room where the majority of the work gets done in quiet reflection, risk the unknown city’s welcome, risk the bloat and glutting of road-miles, and go Willy Loman some poems.

On this trip, we heard about the bombings in Boston and the explosion in West, Texas. The car was quiet and it seemed like such a messed up way to start a trip to read poems to students, and poetry fans, and the unwitting drop-ins. We texted our friends to make sure everyone was okay, and we stared out the window at the clouded-over sky. Poetry never feels like the sharpest tool. It’s not the knife, or the needle, but at some point it does open us, when we’re ready, when the world wants back in. Slowly all the words wiggled back into our chests like helpful road signs after miles of nothing, but skyline.

Choosing poetry sometimes feels like having joined the circus. I eat fire. They eat swords. Together we make a few dollars for gas and laugh a lot with the small, but rowdy crowd. Just recently, on our poetry tour through the American South, I said to Adam Clay and Michael Robins, “Do you ever feel like you’re wearing less of an outfit and more of a costume?” Which was true that day. We were in Oklahoma and I was wearing gingham and things started to feel weird. That day, our waiter looked exactly like my Grandpa Frank (Francisco before he changed it) and I could hardly stop staring at him for how remarkable the resemblance was. Time shifted. Strange movie with a good director. Nothing was not the world talking directly to us.

People like to tell stories about writers, especially the ones who were, or are, particularly nuts. On the road, you hear about a short story writer who once played Russian Roulette with his workshop students, the poet that required a 6-pack of beer at the podium whenever he read, the glory, glory, and the gory of how messed up we all are, how ill-suited for the world. We aren’t famous writers, by any means, but we’re working writers so people like to know about our lives. It’s hard to explain to someone that you like to have quiet nights in, make a nice cheap dinner, hold hands, work out a little, watch some TV, pet the dog. When what you’re saying is that an amazing life can be a quiet one, a balanced one, a live-able one, it sounds made up, like the moon landing. It should all look more impossible.

On the road, people want to ask you about making a living. There’s talk about teaching and how to scrape by. That’s the hard part about it, no one’s getting rich on poetry, but maybe that’s the awesome part, too? It’s an incredibly honest art. To quote Gregory Orr: “How lucky we are/that you can’t sell/ a poem, that it has/ no value, might/ as well/ give it away./ That poem you love./ That saved your life. /Wasn’t it given to you?” In Austin, Texas an Eighth Grader asked, “Then why do you do it? If it’s not for money or fame?” And I said, “We do it because we want to deeply connect with other people, people like you.” She told us she liked the love poems the most. Then, we hit the road again.

Writing can be so lonely. And it can feel at times very selfish, or even foolish. It’s not that you have to feel important to write, but you have to value yourself enough, even for the brief moment of composition, to believe that time dedicated to poetry is not wasted time. Overcoming that hurdle, that pinch at the back of the throat that’s telling you to do something else of more social or monetary value, is an essential part of the writing process. When we’re on tour, all of that becomes even clearer. We see our work connecting. The young woman who came up to me and told me how important it was to hear Spanish in a poem, how as a Mexican American in the middle of Kansas, that somehow felt really significant. No other world than this one. No way to live if not by living.

By the end of the tour, eyes puffy from lack of sleep and late nights, I almost didn’t want it to end. As much as I missed my dog and my man, it seemed like the road had become another way of binding us all together. After meeting so many people and hearing their stories about writing and getting by, it felt like maybe something had shifted. Sometimes, as a writer, as a human, you need to know that everyone feels plagued by their own particular past, or guilty over old mistakes, or wounded by the world, and that everyone has some odd heartbreak stuck in a shoebox at the bottom of the closet, and a stinging needle of desire somewhere in the veins. All these towns are full of strangers swinging in the sticky wonder of America and it’s okay to love every suffering and surrendering part of them.

Two days ago, I was at the nail salon and the woman next to me heard me explain to someone that I was a writer. She asked what I wrote about. I shrugged and said, “The usual: Death, Love, Grief, Terrible Wonderful Life.” She was a nurse and she seemed to understand that. Then, she talked a lot about the book she was reading about Heaven and how it was real. All the women in the room perked up. They had all read this book about Heaven. They loved it. They were smiling now and excited. They wanted to know if I wrote about God. I am an atheist, so I don’t really. But I thought we could talk about love. We talked about a friend’s heartbreak and all the women nodded and we got our nails done, spoke about the heart and all its ways of getting messed up and wrecked and then right again, and felt really close for a brief second. “You should write about this,” the woman said. “About how we all understand the hurt.” I said I would. I said, “That’s the part that helps.”

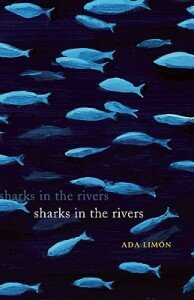

Ada Limón is the author of three collections of poetry, SHARKS IN THE RIVERS, THIS BIG FAKE WORLD, and LUCKY WRECK. She has received fellowships from the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and won the Chicago Literary Award for Poetry. She is currently finishing her first novel, a book of essays, and a fourth collection of poems. She works as a writer and lives in Kentucky and California.

Love the book!!!