For a short three years of my life, my friends were poets. Maybe not all of them, but the ones who weren’t poets were essayists or novelists, and poetry wasn’t a bad word among us. We all read poetry, went to readings, talked about this new writer or that piece, wrote poems or stories or both. We also bitched about our bosses, celebrated each other’s birthdays, went jogging when the weather lifted above freezing and we felt we’d maybe run out of things to write. We drank, ate, fucked, sometimes danced, went to the movies, gossiped, despaired, told dirty jokes, congratulated one another on our small successes, envied each other the same, talked about our families, caught and missed buses—in other words, we lived our lives like everyone else. Then we all finished grad school and, with MFAs in hand, moved toward the compass point that promised the most luck or the least terror.

For a short three years of my life, my friends were poets. Maybe not all of them, but the ones who weren’t poets were essayists or novelists, and poetry wasn’t a bad word among us. We all read poetry, went to readings, talked about this new writer or that piece, wrote poems or stories or both. We also bitched about our bosses, celebrated each other’s birthdays, went jogging when the weather lifted above freezing and we felt we’d maybe run out of things to write. We drank, ate, fucked, sometimes danced, went to the movies, gossiped, despaired, told dirty jokes, congratulated one another on our small successes, envied each other the same, talked about our families, caught and missed buses—in other words, we lived our lives like everyone else. Then we all finished grad school and, with MFAs in hand, moved toward the compass point that promised the most luck or the least terror.

For me that meant moving back to Seattle where I had a paycheck waiting and friends I’d left behind. Though the job I was coming back to had nothing to do with writing, at least I had a job in a time when economic uncertainty was becoming the norm. And unlike when I up and moved to Minneapolis for school, at least I was returning to a city that wasn’t an unknown. It was comforting to come back to a place I knew, to people I knew.

For me that meant moving back to Seattle where I had a paycheck waiting and friends I’d left behind. Though the job I was coming back to had nothing to do with writing, at least I had a job in a time when economic uncertainty was becoming the norm. And unlike when I up and moved to Minneapolis for school, at least I was returning to a city that wasn’t an unknown. It was comforting to come back to a place I knew, to people I knew.

Actually, no—it wasn’t. Because from the first day back I realized they didn’t know me.

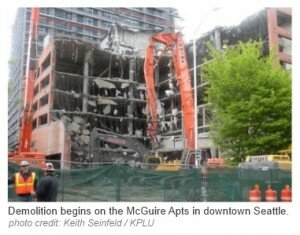

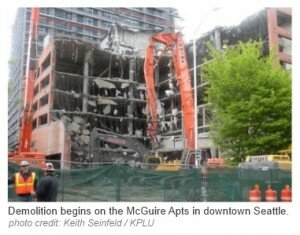

It wasn’t completely their fault. Even before grad school, I didn’t tell many people about my writing—I wasn’t hiding it exactly, it just didn’t seem to come up. My co-workers were more focused on whether or not that sponsor had signed on to bankroll the new website we’d already started producing or if I was going to that team morale event at the go-kart track. My friends wanted to know whether our skyscraper apartment building really was being demolished because of unsafe construction (it was), how my new old-job was going especially with that commute over the bridge getting worse, if I’d tried that recently opened restaurant that sourced all their food from no more than 360 miles away, and if I was going to so-and-so’s baby shower next weekend or you-know-who’s housewarming party. The couple of times I suggested going to a reading, everyone feigned a bit of enthusiasm; nobody showed.

When the layoff rumors came true and I no longer had a corporate job neatly summed up on a business card with a recognizable company logo, I decided to try writing full time—at least until my savings ran out or my husband decided that being the sole breadwinner was overrated. But when people I met asked what I did for work, I was reluctant—no, I was loathe to say, “I’m a poet.” Based on the few times I’d tried answering that way, I knew that whatever fanciful ideas were conjured in their heads about what being a “poet” was, it wasn’t remotely close to the reality of it. So I’d say I was a “writer” and then rush off before they could ask what I wrote. I could have gently corrected their misunderstandings about peasant blouses, love and sunsets, end-rhymes centered down the page, the tears of orphans mixed into our ink wells, but I guess I was tired of doing that. Or maybe I was out of practice after the three years I’d spent not having to explain. Or maybe I felt that even if I tried, even when I tried, it didn’t change anything. It didn’t stop them from telling me how they, too, wrote poetry when they were feeling sad or from abruptly proclaiming, “ ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, took the one less traveled…’ ” then looking to me for some kind of consent. It didn’t prevent them from asking incredulously if people read poetry anymore or blurting out in amazement, “Wow. Really? I didn’t know that still existed!”

When the layoff rumors came true and I no longer had a corporate job neatly summed up on a business card with a recognizable company logo, I decided to try writing full time—at least until my savings ran out or my husband decided that being the sole breadwinner was overrated. But when people I met asked what I did for work, I was reluctant—no, I was loathe to say, “I’m a poet.” Based on the few times I’d tried answering that way, I knew that whatever fanciful ideas were conjured in their heads about what being a “poet” was, it wasn’t remotely close to the reality of it. So I’d say I was a “writer” and then rush off before they could ask what I wrote. I could have gently corrected their misunderstandings about peasant blouses, love and sunsets, end-rhymes centered down the page, the tears of orphans mixed into our ink wells, but I guess I was tired of doing that. Or maybe I was out of practice after the three years I’d spent not having to explain. Or maybe I felt that even if I tried, even when I tried, it didn’t change anything. It didn’t stop them from telling me how they, too, wrote poetry when they were feeling sad or from abruptly proclaiming, “ ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, took the one less traveled…’ ” then looking to me for some kind of consent. It didn’t prevent them from asking incredulously if people read poetry anymore or blurting out in amazement, “Wow. Really? I didn’t know that still existed!”

The truth was, neither did I. Read more…

![(I was reading a friend's manuscript to offer a critique. Those notes are on the top left side: “Sarah's poems: caves/depth/rot-softness-not necessarily a positive attribute/ears, disjointed body/insides of things/dankness/mineral/telephone/[illegible]/animal”. Below that, a to-do list and “now we are/ old enough/we know/we can die”. On the right-hand side of the page, some drawings and to-do lists.)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/2.jpg)

![(From a very recent notebook. The far left page: part of the novel I am working on [“Approaching Naples in a...]. The page that is vertical looks like reading notes of some kind. On the right-hand page, working out plot or connections between elements in the novel. Middle of the page: “socialization for subservience | 1619” [I am not sure any more what that date means there] and then below that “getting to know dates the way/some writers know characters/ the century”.)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/6.jpg)

![(The notebook I am using now. I sometimes find the squares hard to write on, somehow constricting. This is me working out where things might go in the novel I am working on. From top down: “APRIL—STILL//[Public Record] 3480// [Film Stills/inside tsunami] 823// [FIRST THINGS FIRST] 536//[LiST of SURViVoRS] 1819// [SNOW] 1492 // [AFTER QUAKE/ON ROAD] // [Blandinsky?] 3097 // [MODES OF COUNTING] 2231 // [SHe sees HIM] 189 // [DEATH CERTIFICATES] 1191 // [B'sky?] // [Book of Beginnings] 3778 // [RAIN] 842// [Dictionary]”.)](/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/4.jpg)