“There’s no money in poetry – but there’s no poetry in money, either” –Robert Graves

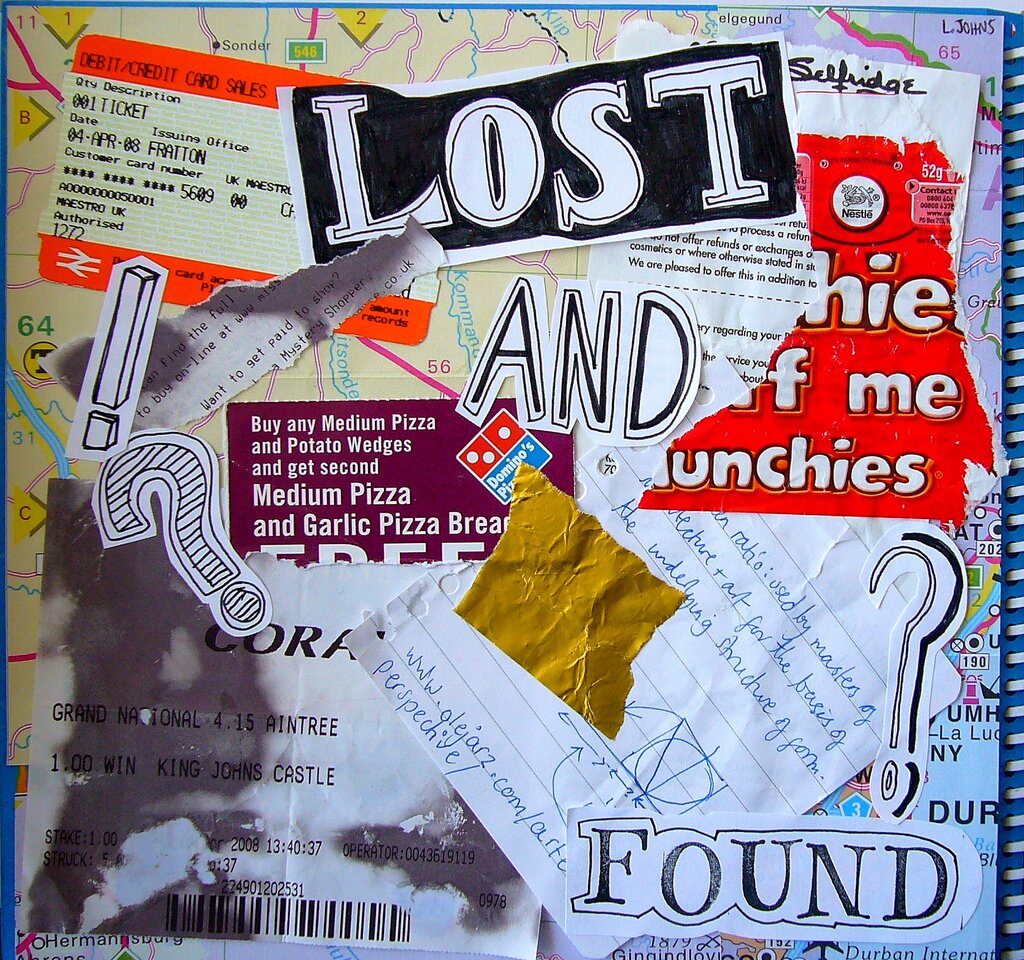

In the late 1970s, while finishing high school, I resolved to write at least one poem a month.

In 1981, as an undergrad at what is now Curtin University, I took a class in writing poetry which required us to write at least one poem a week.

For the rest of the 1980s, I think I averaged one poem a year. In the 90s, closer to one a decade. Since 2001, it’s been one per century, possibly even one per millennium. What happened?

My experience in that class was not unique. Other West Australian novelists I’ve spoken to credit the same tutor with inspiring them to concentrate on writing prose. So why was he even more successful at discouraging aspiring poets than the structuralist lecturer who spoke about ‘the death of the writer’ with the same sort of dreamy optimism that normal people use when talking about winning Lotto (or an Ozco grant)?

It probably helped that the tutor for the short story writing class, the late lamented Mike Henderson, did inspire us to write short fiction, in part by being willing to read as many short stories as we wrote but only grading us on our best three. I suspect, though, that it has more to do with the way the other tutors made us think about why we write what we write, as well as how. This is no bad thing, and it made me realise that many of my reasons for wanting to write would not be satisfied by poetry.

It doesn’t necessarily help to think too much about this question before you write, but it can be valuable after you’ve finished a first draft and are wondering what to do with it. Sometimes we write just for the act of writing, or to try something different. After you’ve finished the first draft, ask yourself who would want to read it? Who would benefit from it? Granted, if you’re J.R.R. Tolkien, there’s a chance that your son will try to turn your shopping list into a bestseller, but few of us have that sort of following. Sometimes a poem or other missive is meant for only one other person. Sometimes the market, the “ideal reader”, for a work is the writer and no-one else, and I’m fairly sure this was true of most of the poetry I’ve ever written. To put the question another way, ask yourself whether you would want to read your poem it if it had been written by someone you’d never heard of before.

The best advice I can give writers is “Ask yourself what you would want to read, and try to write that.” Barring occasional experiments, I’ve tried to stick to that rule with my fiction and even much of my non-fiction.

This doesn’t mean that learning to write poetry isn’t valuable for prose writers. Haiku taught me to be succinct (one novelist I know writes haiku between his trilogies, for the same reason). Sonnets taught me the perfect structure for an argumentative essay. Rewriting short stories into iambic pentameter rhyming couplets à la The Canterbury Tales taught me how important sound and rhythm could be to writing an action scene. The villanelle* (I wrote two that I liked before calling it quits) taught me the use of repetition and ambiguity and the value of a single line.

Publishing poetry, however, is a different beast entirely. The best piece of advice I ever received about that came from the novelist John Marsden, who confessed to a long-held desire to have a poem professionally published. It occurred to him that if he placed one of his poems in one of his novels and the editor didn’t remove it, that would count as professional publication. So I inserted one of my old poems into my next novel, SHADOWS BITE. The rest, I think, can stay in a file in my desk drawer.

* It may be an indication of just how difficult it is to write a good villanelle that my spellchecker didn’t recognise the word, though it had no problem with “iambic pentameter”.

- Stephen Dedman is the author of the novels THE ART OF ARROW CUTTING, SHADOWS BITE and A FISTFUL OF DATA, and more than 120 short stories published in an eclectic range of magazines and anthologies. He has won two Aurealis Awards and an Australian Science Fiction Achievement Award, and been shortlisted for the Bram Stoker Award, the British Science Fiction Association Award, the Seiun Award, the Sidewise Award, and the Spectrum Award. He teaches creative writing at UWA and foundation units at Murdoch University, and has been an associate editor of Eidolon, the fiction editor of Borderlands, the book buyer for most of Perth’s science fiction bookshops, an actor, a game designer, and an experimental subject. He enjoys reading, travel, movies, talking to cats, and startling people.