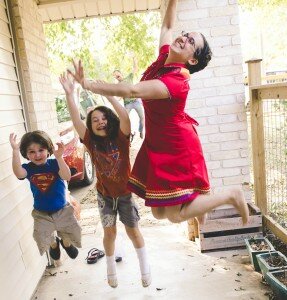

Featured today is cool-cat Emma Haller and her poem, DRIFTING. Below we have a conversation about poetry and how sexuality inspires Haller’s poetry. Here at Metre Maids love having discussions surrounding poetry and where our poets feel their poetry comes from. We each have a different place that we pull stuff from, and it’s still important to talk about. Without further ado:

DRIFTING

Strength holds me,

a coin among the cloud,

shoulders wide and engulfing.

Freckles she once hid,

shine bright,

the Sun and I kissing her elbows in cheeky glee.

Waves creep up,

flew back,

and distill.

I half smile,

feeling myself drifting, towards an unsullied place.

I clasp her hip,

hold my breath in the tenderness,

the opportunity of her world.

A sadness lingered,

I hope for clarity.

Phantom limbs,

scrambling together as one.

How did ‘Drifting’ come to be?

Moving from one relationship to another, it caused a re-evaluation of every facet of my life, and it was a significant and intense relationship so I wanted to capture a sense of that. I tried to convey that new relationships have a wonderful crisp edge to them, the butterflies and all those cliches are real.

How does your sexuality inform your poetic imagery?

I think sexuality is fluid and informs everything I do. My emotions, I’ve come to realise are important, and sometimes you need to let whatever feelings you’re having inform your day-to-day life. My sexuality is vital to who I am as a person and I try to channel feeling however I am able.

What poet do you most look up to and why, how do they speak to you?

Gwen Harwood is a main influence for me, I studied her a lot throughout school. Her poetry has a lovely naturalistic quality and has always been relaxing to read. Also a bit of Emily Dickinson as well, apparently she was obsessed with white clothing which is fun, Judith Wright’s poetry is also engaging.

What is your editing process like?

I read the poem out and try to gauge it’s sound and meaning for the reader/audience. I edit as I go, usually on a computer but I edit a lot in my journal. All my ideas are written down first, then I piece the stanzas together if I see some links or interesting connections.

What is the best tip you’ve received for dealing with critique?

Focus on what you are trying to convey. I’m learning strategies to be able to teach poetry, and putting myself in my student’s shoes is important every now and then. Critique is important and discussions around interpretations have always been enjoyable. I love teaching and writing, they are large parts of my life and wouldn’t have it any other way.

Emma Haller, a curious observer from childhood, grew up on the Mornington Peninsula where coastal living and traditional Aussie charm helped shape an evocative voice. Her poetry explores the manifold nature of human emotions and poems such as ‘Drifting’ seem to offer contemporary thoughts on relationships as being beautifully despondent experiences. There is an emotional truth that lingers throughout her poems, memorable for their honesty and stunningly constructed design. Currently, Emma is completing a double degree in Arts/Education (Secondary) at Monash University (Melbourne, Australia) and writes poetry in her spare time.