© Claire Sambrook.

It all started with a box of teeth-whitening strips.

In graduate school, my friends and I coordinated a small, online writing group where we would take turns posting and responding to a prompt of the week. On the particular week in question, we were challenged to write a poem using only the words found on product packaging.

Initially skeptical, I reached for the nearest product in my apartment, copied down all of the words from the box and began rearranging. Within half an hour, I had unwittingly written my first found poem. Not only that, I’d actually had fun doing so.

Later, whenever I would find myself struggling to write something original, I would turn to found poetry as an exercise, a way to unclog the creative pipes. Eventually, I began practicing it nearly exclusively, crafting poems from speeches, menus, Twitter streams and more.

In 2011, my own experiences writing and publishing sparked the idea for the Found Poetry Review, a venue designed to showcase how individuals are finding poetry in existing and everyday sources, and to encourage people to write their own found poems.

So, What Is Found Poetry Exactly?

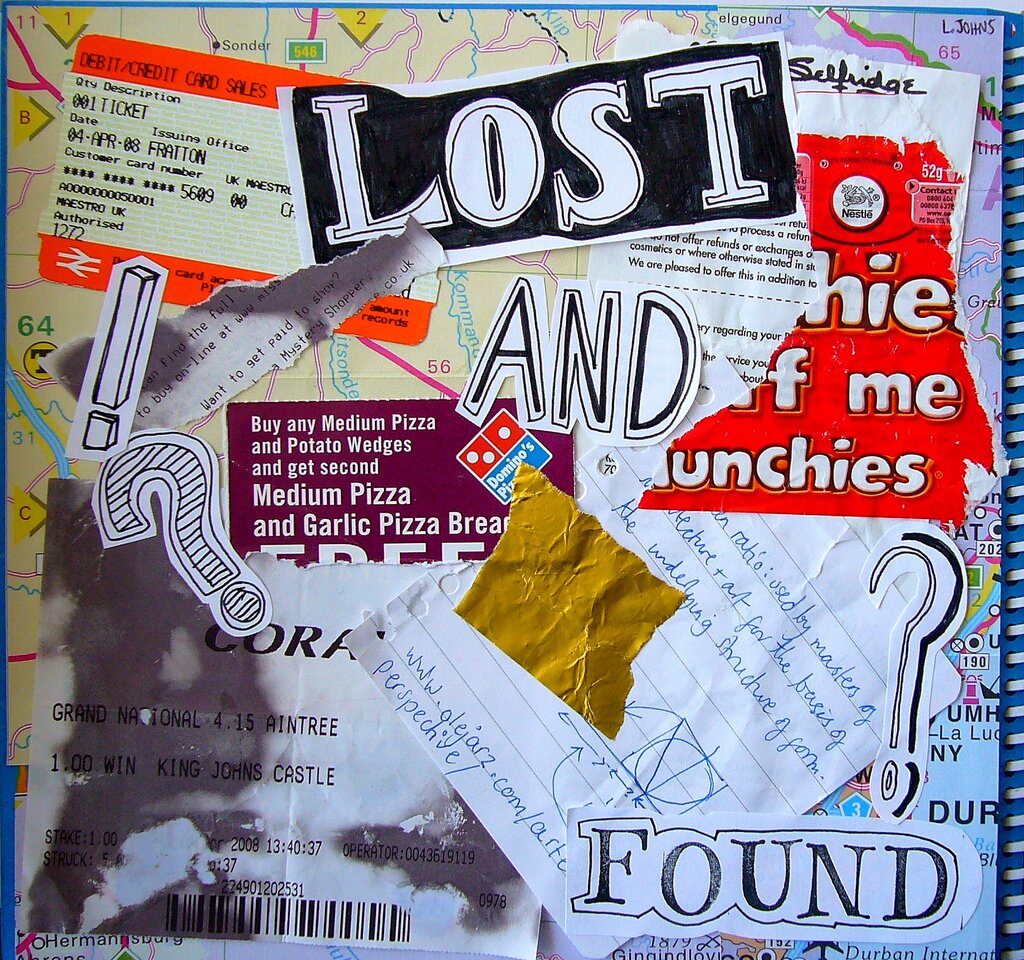

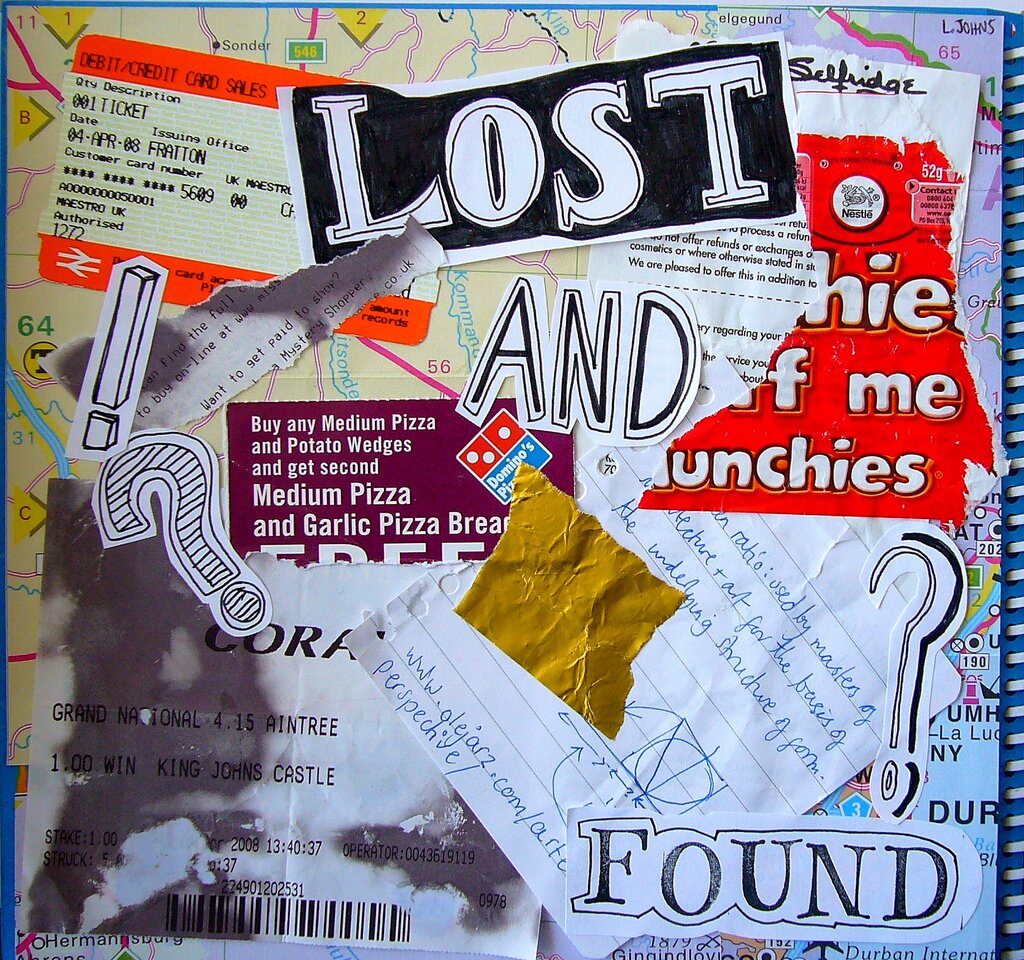

Most definitions of found poetry – sometimes called erasure poetry or blackout poetry – employ a collage metaphor to describe how poets cut out words and phrases from texts and stick them together to create something new.

Invoking safety scissors and glue stick projects gets the basic mechanics across, but doesn’t do a great job of conveying found poetry’s intentionality and art. My favorite description comes from Annie Dillard’s introduction to her collection of found poems, MORNINGS LIKE THESE:

Those happy poets who write found poetry go pawing through popular culture like sculptors on trash heaps. They hold and wave aloft usable artifacts and fragments: jingles and ad copy, menus and broadcasts — all objet trouvés, the literary equivalents of Warhol’s Campbell’s soup cans and Duchamp’s bicycle. By entering a found text as a poem, the poet doubles its context. The original meaning remains intact, but now it swings between two poles. The poet adds, or at any rate, increases the elements of delight. This is an urban, youthful, ironic, cruising kind of poetry.

Not only does Dillard’s definition provide a clearer picture of both found poetry and the people who write it, but it also gives us a better understanding of its detractors. Editors who will inevitably cry “plagiarism!” and “unoriginal!” are but a few branches down the family tree from the conservative art critics who turned up their noses at readymade and pop art in the mid-twentieth century.

Finding a Good Poem

© Jake Bouma.

Imposing parameters or restrictions on experimental writing like found poetry is usually considered bad form; however, working on the The Found Poetry Review has forced me to make decisions about what I consider a quality poem.

I’d put the types of submissions we receive into three broad buckets:

1. Reportage: These pieces excerpt sequential lines from a source text, with the primary intervention being the addition of line breaks or spaces. Photographs of juxtaposed signs or graffiti also fall into this group.

2. Distillation: Poems in this category take words and phrases from a source text, rearranging them into a final piece that retains the text’s general message but is arranged in a new way.

3. Reinvention: Submissions falling into this group take words and phrases from a text, but arrange them in ways so that the poem’s meaning has little or nothing to do with that of the source material.

Most of the poems we accept at The Found Poetry Review come from the second and third groups. When evaluating traditional poetry, editors look for originality in words and sentiment; in found poetry, I look for originality in arrangement. What can you add to the source material? What new story can you find within the original?

Poems from the first group are problematic for me, both as an editor and a writer of found poetry. Singling out a pithy paragraph in Lolita, pressing the return key a few times and calling it a found poem doesn’t do much for me on the editorial front – it’s not surprising or inventive. More significantly, as someone who writes found poetry and tries to build a case for it’s value and art, I see these “reportage” poems as walking too fine a line between plagiarism and ingenuity.

Where to Begin: Crafting Your First Found Poem

Because found poetry is experimental and so individual, I encourage curious writers to jump in first and read examples from the field later. You need to play around before you can get serious.

Since you’re presumably reading this post on the Internet, Wave Books’ erasure tool is a great place to start digging. There, you can choose one of 20 source materials to work with, then use an interactive tool to click and erase words from the text until you arrive at a final poem.

When working electronically from a web-based source (Project Gutenberg, with it’s wealth of public domain source texts, is a good place to begin), you can also consider pulling up two windows side by side – one with your source text and the other with a blank Word document. Skim through the text quickly, copying over into the document interesting words and phrases. Condense and reorder those snippets to create your found poem.

Offline, approach any text – from your morning newspaper to your favorite book to your pile of junk mail – with a pen in hand. As you read, underline or circle words and phrases, then try to work them into a poem. You also have permission to get out those scissors I referenced at the beginning of this post – cut up texts into strips, mix them up and then physically rearrange them on a board or table.

Enlarge Your Practice by Learning from Others

After you’ve taken some time to play around and understand your natural instincts when it comes to writing found poetry, take the time to read what others are doing in the field. Seeing how other writers approach the same art form – and perhaps even the same texts – will help you enlarge your practice.

Below is a short list of some published works of found poetry to buy online or request from your local library:

- A HUMUMENT by Tom Phillips (began in 1970)

- RADI OS by Ronald Johnson (2005)

- A LITTLE WITE SHADOW by Mary Ruefle (2006)

- THE O MISSION REPO by Travis McDonald (2008)

- THE MS OF MY KIN by Janet Holmes (2009)

- NETS by Jen Bervin (2010)

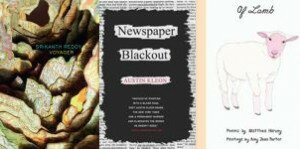

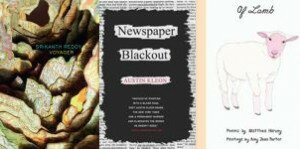

- NEWSPAPER BLACKOUT by Austin Kleon (2010)

- OF LAMB by Matthea Harvey and Amy Jean Porter (2011)

- VOYAGER by Srikanth Reddy (2011)

Online journals such as The Found Poetry Review and Verbatim Poetry also feature plenty of examples from other poets that may spark an idea for your own work.

Finally, be sure to let others learn from you. Post your found poetry on your blog or website, introduce it to your writing group and submit your works to online journals for publication. If you’re a teacher, try a found poetry exercise with your class.

If you’ve written found poetry or have favorite pieces from others to share, be sure to post the text or a link in the comments section below!

Jenni B. Baker.

Jenni B. Baker is the founder and editor-in-chief of the Found Poetry Review. Her poetry has appeared in over a dozen publications, including InDigest Magazine, The Newport Review, qarrtisiluni and BluePrintReview. She is currently working on a manuscript of found poetry derived from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, titled Fest.