Poetry Exists! Poetry & Singing Cats & Oranges and Tiny Hands Exists. & Poetry Exists. Arlene Kim on, Well, the Existence of Poetry!

For a short three years of my life, my friends were poets. Maybe not all of them, but the ones who weren’t poets were essayists or novelists, and poetry wasn’t a bad word among us. We all read poetry, went to readings, talked about this new writer or that piece, wrote poems or stories or both. We also bitched about our bosses, celebrated each other’s birthdays, went jogging when the weather lifted above freezing and we felt we’d maybe run out of things to write. We drank, ate, fucked, sometimes danced, went to the movies, gossiped, despaired, told dirty jokes, congratulated one another on our small successes, envied each other the same, talked about our families, caught and missed buses—in other words, we lived our lives like everyone else. Then we all finished grad school and, with MFAs in hand, moved toward the compass point that promised the most luck or the least terror.

For a short three years of my life, my friends were poets. Maybe not all of them, but the ones who weren’t poets were essayists or novelists, and poetry wasn’t a bad word among us. We all read poetry, went to readings, talked about this new writer or that piece, wrote poems or stories or both. We also bitched about our bosses, celebrated each other’s birthdays, went jogging when the weather lifted above freezing and we felt we’d maybe run out of things to write. We drank, ate, fucked, sometimes danced, went to the movies, gossiped, despaired, told dirty jokes, congratulated one another on our small successes, envied each other the same, talked about our families, caught and missed buses—in other words, we lived our lives like everyone else. Then we all finished grad school and, with MFAs in hand, moved toward the compass point that promised the most luck or the least terror.

For me that meant moving back to Seattle where I had a paycheck waiting and friends I’d left behind. Though the job I was coming back to had nothing to do with writing, at least I had a job in a time when economic uncertainty was becoming the norm. And unlike when I up and moved to Minneapolis for school, at least I was returning to a city that wasn’t an unknown. It was comforting to come back to a place I knew, to people I knew.

For me that meant moving back to Seattle where I had a paycheck waiting and friends I’d left behind. Though the job I was coming back to had nothing to do with writing, at least I had a job in a time when economic uncertainty was becoming the norm. And unlike when I up and moved to Minneapolis for school, at least I was returning to a city that wasn’t an unknown. It was comforting to come back to a place I knew, to people I knew.

Actually, no—it wasn’t. Because from the first day back I realized they didn’t know me.

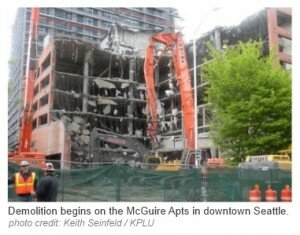

It wasn’t completely their fault. Even before grad school, I didn’t tell many people about my writing—I wasn’t hiding it exactly, it just didn’t seem to come up. My co-workers were more focused on whether or not that sponsor had signed on to bankroll the new website we’d already started producing or if I was going to that team morale event at the go-kart track. My friends wanted to know whether our skyscraper apartment building really was being demolished because of unsafe construction (it was), how my new old-job was going especially with that commute over the bridge getting worse, if I’d tried that recently opened restaurant that sourced all their food from no more than 360 miles away, and if I was going to so-and-so’s baby shower next weekend or you-know-who’s housewarming party. The couple of times I suggested going to a reading, everyone feigned a bit of enthusiasm; nobody showed.

When the layoff rumors came true and I no longer had a corporate job neatly summed up on a business card with a recognizable company logo, I decided to try writing full time—at least until my savings ran out or my husband decided that being the sole breadwinner was overrated. But when people I met asked what I did for work, I was reluctant—no, I was loathe to say, “I’m a poet.” Based on the few times I’d tried answering that way, I knew that whatever fanciful ideas were conjured in their heads about what being a “poet” was, it wasn’t remotely close to the reality of it. So I’d say I was a “writer” and then rush off before they could ask what I wrote. I could have gently corrected their misunderstandings about peasant blouses, love and sunsets, end-rhymes centered down the page, the tears of orphans mixed into our ink wells, but I guess I was tired of doing that. Or maybe I was out of practice after the three years I’d spent not having to explain. Or maybe I felt that even if I tried, even when I tried, it didn’t change anything. It didn’t stop them from telling me how they, too, wrote poetry when they were feeling sad or from abruptly proclaiming, “ ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, took the one less traveled…’ ” then looking to me for some kind of consent. It didn’t prevent them from asking incredulously if people read poetry anymore or blurting out in amazement, “Wow. Really? I didn’t know that still existed!”

When the layoff rumors came true and I no longer had a corporate job neatly summed up on a business card with a recognizable company logo, I decided to try writing full time—at least until my savings ran out or my husband decided that being the sole breadwinner was overrated. But when people I met asked what I did for work, I was reluctant—no, I was loathe to say, “I’m a poet.” Based on the few times I’d tried answering that way, I knew that whatever fanciful ideas were conjured in their heads about what being a “poet” was, it wasn’t remotely close to the reality of it. So I’d say I was a “writer” and then rush off before they could ask what I wrote. I could have gently corrected their misunderstandings about peasant blouses, love and sunsets, end-rhymes centered down the page, the tears of orphans mixed into our ink wells, but I guess I was tired of doing that. Or maybe I was out of practice after the three years I’d spent not having to explain. Or maybe I felt that even if I tried, even when I tried, it didn’t change anything. It didn’t stop them from telling me how they, too, wrote poetry when they were feeling sad or from abruptly proclaiming, “ ‘Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, took the one less traveled…’ ” then looking to me for some kind of consent. It didn’t prevent them from asking incredulously if people read poetry anymore or blurting out in amazement, “Wow. Really? I didn’t know that still existed!”

The truth was, neither did I.

When I ventured to talk about poetry to my friends—books I’d read or pieces I was trying to write—their eyes hung up on me like dual dial-tones. They’d nod and smile politely, but were careful not to engage, the way you might silently indulge a friend’s strange fetish or endure the uncomfortable talk of their addiction therapy. When they offered a lukewarm, “Oh, uh-huh, interesting,” then sipped desperately at the waning ice cubes in their drink, I’d figure they’d suffered enough and I’d move on to less freakish subjects. But I was starting to feel that part of me ceasing to exist. I was wondering if it had ever existed.

It wasn’t that I didn’t know any writers or poets—I had rejoined my long-standing Monday night writing group when I moved back, but we seemed to exist only once a week to one another, if that. And though I’d count them among my friends, for some reason, we didn’t hang out aside from Mondays. They weren’t as involved in my everyday life, nor I in theirs. Having this fringe group almost exacerbated the feeling that I was splitting into two, and that one of the two sides was imaginary.

But we all live with imaginary sides, or at least, sides of us that don’t come out that often even among friends. That I could live with, especially after the Edenic nostalgia of grad school faded into more routine memory. And I could live with having a job that was frequently misunderstood. I wasn’t alone there either. How many times had I witnessed someone ask my husband what he did for work and then respond to his answer of “I’m a computer programmer” with “Hey, so I’m having trouble hooking up my printer to this new laptop I got—do you know what’s going on there?” Instead of explaining that developing database software isn’t the same thing as being an I.T. pro, he usually tries to be understanding—as do I when my friends say to me, “I’m sorry, Arlene, but, the whole poetry thing is too hard—I mean, I try but I just don’t get it.” In these moments, I think to myself, “OK, poetry isn’t everyone’s thing. No need to get upset or self-righteous about it. I’m gonna try to understand where they’re coming from.”

But then last year, I came to realize something that changed my previously sympathetic mind. It happened shortly after this beguiling song and dance invaded all our lives:

Yep. Remember when everyone you knew was suddenly making a parody video of Psy’s Gangnam Style, or repeating the phonetically memorized lyrics to you (which is particularly weird if you speak Korean and you know they don’t), or breaking out in the horsey dance during dinner?

Having grown up in a place and time when being “Oriental” was akin to being extraterrestrial but not as cool, when the only two Asian countries that existed in people’s minds were China (because everything was made there even back in the early 80s) or Japan (because a “Jap” probably killed your grandfather), I was sort of shocked to find a Korean pop song getting this sort of spirited reception. But the real shocker was when months after it had already gone viral (I tend to be late to the party on these Internet trends—in fact, I wouldn’t even know about the party if it weren’t for my non-poet friends), I finally watched the video.

When the screen faded to black, the first thing I thought was: WTF?! You don’t “get” poetry because it’s too “hard” for you, too mysterious, but this, you “get”? The lyrics aren’t even in your language! The horse dance has nothing to do with what he’s saying! You don’t know what 강남 or 오빠 means! But all that’s OK with you? No—it’s more than OK—you like it—you take time out of your day to dance it in front me, to watch interviews with Psy about what inspired him, to look up the meaning of the lyrics, to locate the Gangnam neighborhood via Google Earth, yet this eludes you:

Suddenly, I recalled every meme and video forwarded to me by the very friends who’d been shunning poetry, claiming under-developed imaginations and the inability to understand anything but the most literal communication. I wanted to get up in their faces and say:

Suddenly, I recalled every meme and video forwarded to me by the very friends who’d been shunning poetry, claiming under-developed imaginations and the inability to understand anything but the most literal communication. I wanted to get up in their faces and say:

You couldn’t make it through Eliot’s “Waste Land” because the Shantih Shantih shit at the end was too wacky for you plus it was TLDR, but you always name every yoga asana in Sanskrit (“I’ve finally learned how to relax into my Adho Mukha Svanasana”), and after you sent me this, you couldn’t stop singing its hilarious nonsense:

Then when you discovered this, you were beside yourself with happiness:

That night I played Steve McCaffery’s “The Birds” for you, you looked at me like, “Seriously? Sound poetry? Is this supposed to mean anything?” but forwarding this little gem to me, twice, wasn’t enough—you then had to perform it verbatim whenever we met:

You said you don’t read poetry because it feels old, it doesn’t speak to you, it doesn’t seem relevant, but when this came on during the movie previews,

you sat in breathless silence—riveted, teary-eyed. (You know that’s Walt Whitman, right?)

The extended metaphor of Inger Christensen’s alphabet or Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, the over-the-top imagery of Nate Slawson’s Panic Attack , USA, the strange juxtapositions in Heather Christle’s The Trees The Trees are all too much for you to “get,” but not these wonders:

Oh, poetry—it’s just too wacky for you! But not the immaterial joys of inexplicably tiny hands

SNL’s “Lawrence Welk Show” Tiny Hands Video.

or real people with fake arms.

Poems are too abstract, too conceptual! They fool with language like Cathy Park Hong’s Dance Dance Revolution and M. NourbeSe Philip’s ZONG! Your brain can’t take it! Why can’t people just say what they mean in simple words? Like these people whose uncontrived manifesto of action you emailed to me as a beacon of clarity in these semiotically challenging times:

or these people whose simple expressions of those little things—beauty, power, time, uprising, isolation, belonging—you watched again and again with me without complaint or confusion:

What does all this mean? It means, you slacker mofos, that the magic was inside you all along! It means that poetry isn’t dead or un-gettable, but that you’ve decided to close yourself to it in one way even as you were constantly drawn to it in other ways. It means I know you know what I mean when I’m reading you the latest poem that’s turned me on, that coming to a poetry reading with me and enjoying it isn’t beyond you, that the side of me you’ve been trying to pretend doesn’t exist—that I’ve been trying to pretend doesn’t exist—exists; it exists so hard that you can’t help but stop and listen to it, sing it to yourself, recall its silliness at surprise moments, laugh at its jokes, let it make your eyes water, tell all your friends about it every chance you get.

Arlene Kim grew up on the east coast of the U.S. before drifting westward. Her first collection of poems What have you done to our ears to make us hear echoes? (Milkweed Editions) won the 2012 American Book Award. She lives in Seattle where she reads for the poetry journal DMQ Review